线——生命之缕

提及“档案”这一概念,人们脑海中往往会浮现出那些储存、记录历史的文献、箱子与机构。

但如果,养育一个人的过程本身就在创造并丰富着一份档案呢?

《线——生命之缕》进一步探讨了“身体即档案”这一热议话题。身体通过塑造日常生活的具象实践,承载、传递并生成知识、记忆与历史,是一份鲜活生长、可交互对话的动态档案。

祖母、母亲与女儿的身体既是创造之地,也是储存之所,她们编织着知识与记忆的丝线,将其紧密联结。那些由故事、歌谣、手工艺和食物编织而成的“丝线”,不仅记录和传递着个人化的家族档案,更映射、书写并记载了更广阔的文化记忆与历史脉络。

我们可以通过冯颖茹、虞添锦、王雨及赵若希四位艺术家的作品,探索这种“鲜活、具象且母系传承”的档案概念——她们的创作均围绕女性生命历程,以及其中产生和分享的知识与记忆展开对话。

赵若希的作品用丝线编织生殖器官,既传达了生命的起源,也体现了女性步入母亲角色后所肩负的责任。这一“丝线”的具象与隐喻表达,展现了连接、传递和储存记忆与知识的“纽带”,也凸显了身体档案的物质性。

虞添锦则邀请我们探讨,对母亲和祖母的观察如何不经意间塑造并反映我们对自我、社会与文化的理解。她以“镜子”为辩证媒介,探索自省、评判与期待的代际传承——这恰恰印证了,那些塑造日常生活的具象实践,正在不断映照并记录着知识与记忆。

王雨的作品创作构思与制作均有其祖母直接参与,将蒙古族的知识、语言和手工艺重新编织并回归到艺术家的身体与记忆之中。通过蒙古族传统女性手工艺的代际延续,王雨的作品证明,身体是通过表演、姿态和叙事来储存和传递知识、记忆与历史的场所。

冯颖茹的作品则探讨了身体档案的断裂与碎片化——她的创作观察、叙述并介入了女性从记忆、场所和社群中“消失”的现象。在与“遗忘”这一议题对话的同时,冯颖茹的创作也推动了记忆的复苏与回归集体意识的过程,暗示着即便联结的丝线可能变弱,却极少真正断裂。

这条“丝线”既是起源、羁绊,也是跨越代际的联结与束缚——它将祖母、母亲与女儿的生命编织成一份鲜活、具象的身体档案。

艺术家们以针为笔、以线为墨、以纤维为媒介、以图像为织机,共同探索了“丝线”在定义女性身份、家族叙事与历史语境中的复杂作用。

《线——生命之缕》将这些作品与对话延伸至数字与物理空间,带领观众走进祖母、母亲与女儿的共创之地。通过视觉叙事、对话交流,以及对食物和歌谣等多感官记忆的冥想,该项目旨在激活档案的参与性与身体性。

作为项目的一部分,艺术家们受邀分享了那些让她们想起与母亲、祖母共度时光的食物与歌谣。在此,我们也邀请您参与其中,分享那些能带您回到与家人共度瞬间的食物与歌谣,为这份档案编织属于您的“丝线”。这些分享将被整理成食谱集与播放列表,供大家交流互动——共同构建一份鲜活、持久且不断生长的档案,一份我们能够集体践行、各自承载的档案。

身体,终究是创造与储存的殿堂。

When raising the notion of the archive, one’s mind can wander to the documents, the box, and the institutions that store, and record history.

But what if the process of raising a person can create, and contribute to an archive?

Xian – A Thread enters growing conversations that the body itself is an archive. Preserving, transmitting, and producing knowledge, memory, and history, through the embodied practices that contour our daily lives. The body as a living, growing, conversational archive.

At once sites of creation and storage, the bodies of grandmothers, mothers, and daughters weave, and bind knowledge and memory. Threads woven by storytelling, song, crafts, and food, document and transmit not only personal familial archives but mirror, author and record broader cultural memories and histories.

The concept of the archive as living, embodied and matrilineal can be explored through the works of Feng Yingru; Tianjin Yu; Yu Wang and Zhao Ruoxi, all of whom converse with the lifecycles of womanhood, and the knowledge and memories produced and shared throughout.

Zhao Ruoxi’s works weave reproductive organs with thread to convey at once the genesis of life, and the obligations that bind women upon their entrance into motherhood. At once a literal and metaphorical representation of a ‘thread’, Ruoxi’s work demonstrates the connective tissue that creates, transmits, and stores memory and knowledge, and the physicality of the embodied archive.

Tianjin Yu then invites us to explore how observations of mothers and grandmothers inadvertently shape and reflect understandings of self, society, and culture. Through the dialectal medium of the mirror, Yu explores the inheritance of self-examination, judgement, and expectations – speaking to the witnessing of the embodied practices that contour our daily lives to reflect, and record knowledge and memory.

A grandmother is directly involved in the conception and creation of Wang Yu’s work, which re-weaves and returns Mongolian knowledge, language, and craft to the body and memory of the artist. Through the intergenerational continuation of traditional Mongolian female crafts, Yu Wang’s works are demonstrative that the body is a site for storing and transmitting knowledge, memory and history through performance, gesture, and storytelling.

The fracturing and fragmentation of the embodied archive is then explored through the work of Feng Yingru, whose body of work observes, narrates, and intervenes with the disappearance of women from memory, place, and community. Whilst conversing with the phenomenon of forgetting, Yingru’s interventions empower processes of revival and return to the collective consciousness – implying that whilst a thread of connection may be weakened, it is seldom ever lost.

At once the thread is a genesis, a tether, a connection, and constraint that traverses generations – stitching the lives of grandmothers, mothers, and daughters into a living, embodied archive.

The artists wield needles as pens, threads as ink, fibres as mediums, and images as looms, collectively exploring the intricate role the thread plays in defining female identity, familial narratives, and historical contexts.

Xian – A Thread translates these works and conversations into the digital and physical realms, bringing audiences into the spaces of co-creation between grandmothers, mothers, and daughters. Through visual storytelling, conversations, and meditations on multi-sensory memory through recollections of food and song, this project seeks to enliven the archive as participatory and embodied.

As part of this project, artists were invited to share meals and songs that remind them of moments shared with their mothers and grandmothers. As you engage with this project, we invite you to weave your thread within its archive by sharing the meals and songs that transport you to moments shared with yours. These offerings will then be recorded via a form of recipe book and playlist, to which we can all engage with – creating a living, durational, and evolving archive that we can collectively, and individually embody.

At once the body is a site of creation and storage.

内容contents

作品感受 DAWN: 赵若希 RUOXI ZHAO

摇篮 the cradle: 王 雨 YU Wang

七宗罪 the seven deadly sins: 虞添锦

tianjin yu

永恒的针脚 timeless stitches: 王 雨 YU Wang

消失的女性 DISAPPEARED WOMAN: 冯颖茹

YINGRU FENG

蝴蝶效应 the butterfly effect: 冯颖茹

YINGRU FENG

破晓

DAWN

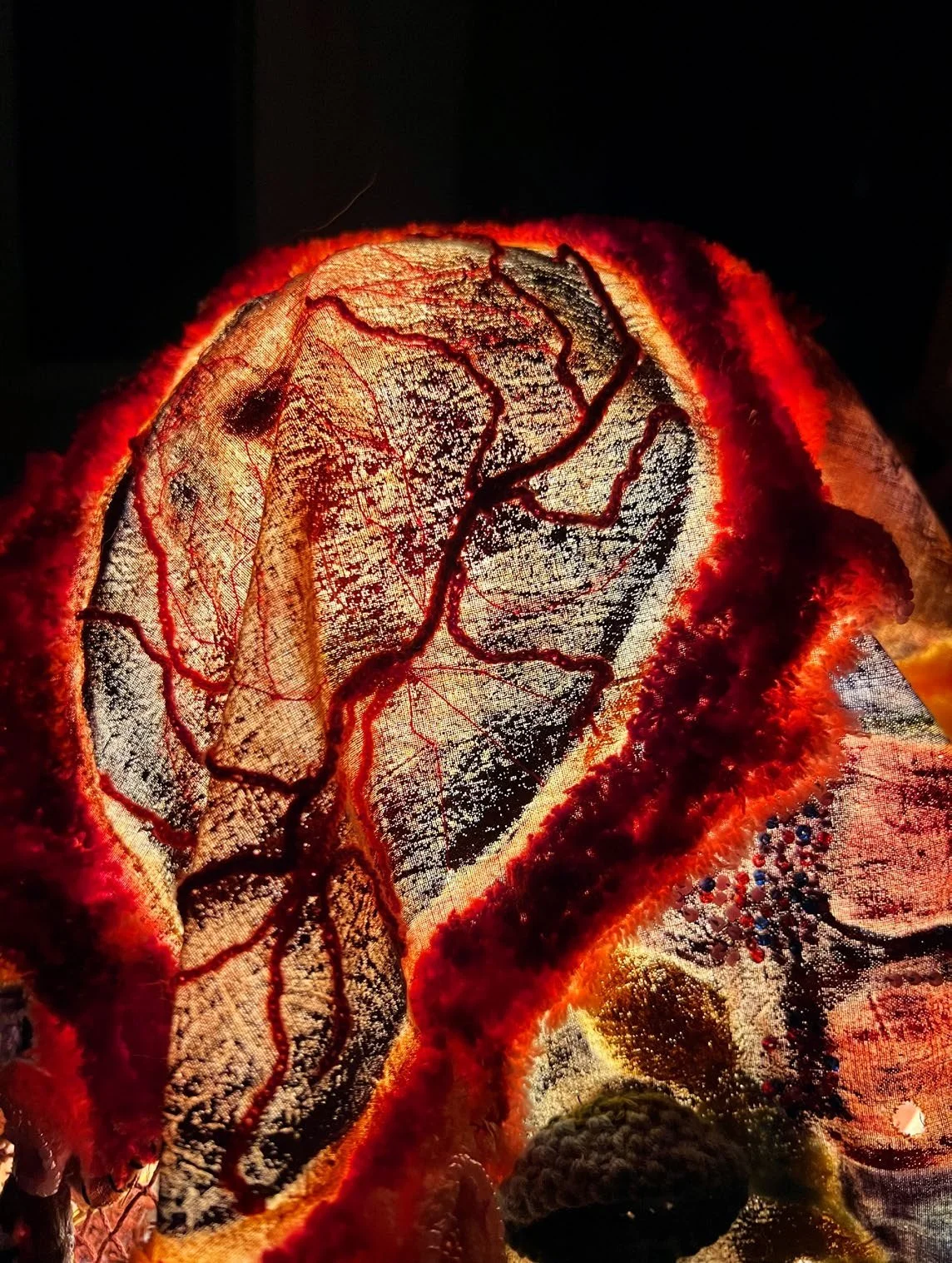

赵若希 RUOXI ZHAO

油画、毛线、丝线、串珠、毛毡等

Oil painting, wool, silk thread, beads, & felt

80 x 80cm, 80cm x 80cm

我的母亲和祖母是我理解女性生存境遇的主要来源。她们在家庭中为琐事奔波的日常,让我直观感受到女性被“家庭责任、生育角色”这些社会枷锁束缚的状态。这种观察成为我作品的核心灵感,我不禁会思考,这样的生活真的是她们内心所愿吗?在我看来,有太多女性被“社会”这一无形的牢笼裹挟前行。

“My mother and grandmother are the main sources from which I understand the living conditions of women. Their daily hustle and bustle over trivial matters at home made me directly feel the state of women being bound by social shackles such as family responsibilities and reproductive roles. This observation has become the core inspiration for my works. I can't help but wonder: Is such a life really what they desire in their hearts? In my opinion, too many women are bound by invisible traps of ‘society’.”

这种观察也成为我作品的核心灵感。比如在我的作品破晓中,我通过一些女性的器官,比如子宫、卵巢、胎盘等女性器官元素,以及一些真菌细菌的繁殖符号,来具象化他们所承受的那些压力,比如一些来自于家庭和生育的,然后进而探讨性别刻板印象下女性的精神桎梏,他们让我更敏锐的捕捉到社会枷锁。

“These observations have become the core inspiration for my artistic works. For instance, in my piece ‘Dawn’, I use female reproductive organs— such as the uterus, ovaries, and placenta — along with symbols of fungal and bacterial reproduction, to concretely represent the pressures women endure, particularly those stemming from family dynamics and childbirth. This exploration further examines the mental shackles imposed on women under gender stereotypes, sharpening my sensitivity to societal constraints.”

我的母亲和我的祖母,我认为如果她们自己的生活不与家庭相关的话,其实是大有可为的。但是我认为她们被家庭束缚的太多了,所以我就是通过这些生活中这些琐碎的事情,来作为我的一部分灵感来源。

My mother and grandmother, who I believe are truly independent individuals, could have achieved much more if they had lived lives separate from family. Yet I feel they were overly constrained by family ties.

选择纤维材料是因为它的物质性与隐喻性高度契合我的创作主题。一方面,纤维的柔软与韧性能直观的表达禁锢与挣脱的张力,比如毛线的缠绕可能象征着社会期待对女性的捆绑,还有那些烧制重制后的布料的破洞则隐喻枷锁的破碎。然后,还有另一方面就是纤维材料带有呃比较带有那种历史感,我用的是那种童年的被子的布料作为接底,然后它会就这些材料会承载一些家庭记忆,与女性在家庭中被规训的主题形成呼应。旧布料基底:隐喻个体在家庭与社会中的身份溯源。它承载着童年与家庭的记忆,却又被改造、重构,暗示女性在“家庭角色”的规训下,既被塑造又试图突破的身份挣扎。同时,纤维的立体编织工艺,像我做的串珠,还有钩织,能与平面油画结合,构建出器官繁殖元素的层次肌理,让挣脱禁锢的过程更具视觉冲击力。

“I chose fibre materials because their materiality and metaphorical qualities align perfectly with my creative themes. The softness and resilience of fibres visually convey the tension between confinement and liberation. For instance, the intertwining of yarns symbolises societal expectations that bind women, while the burnt holes in reprocessed fabrics metaphorically represent broken shackles. Moreover, these materials carry a historical essence. Using childhood quilt fabrics as the base layer, they evoke family memories that resonate with the theme of women's domestic discipline. The old fabric base metaphorically represents the origin of an individual's identity within the family and society. It carries the memories of childhood and family, yet is transformed and reconstructed, hinting at the identity struggle of women under the discipline of ‘family roles’, being both shaped and attempting to break through. The three-dimensional weaving techniques—like beadwork and crochet—combine with flat oil paintings to create layered textures metaphorically represents the layer-by-layer wrapping of reproductive pressure and social expectations. Just as women are constantly burdened with household chores and reproductive responsibilities, the thick texture of the fibres makes this ‘weight of pressure’ perceptible.”

摇篮

the cradle

王 雨 Yu WaNG

摇篮,视频(电视显示器4'36)

Cradle, video (TV display 4’36)

可变尺寸, Variable size

她的这件作品《摇篮》,形式更为抽象,但情感更加深刻。

在这件装置作品中,王雨将传统的蒙古摇篮与红线、以及外祖母唱的蒙古民谣录音结合在一起。

在蒙古文化中,摇篮象征着母性与庇护—— 它是生命开始的地方,是孩子第一次感受到家庭节奏的空间。

但在王雨的作品里,摇篮被红线紧紧缠绕, 那条线既是守护,也是一种束缚,

暗示着跨越几代女性之间的复杂情感张力。

录音中的外祖母歌声,为作品增添了一种极为私密的温度。

王雨告诉我,在蒙古传统中,摇篮曲不仅是一首歌,更是一种记忆的声音。

它承载着语言、情感与文化的延续。

当她把外祖母的歌声嵌入装置中,声音就成了一种无形的线, 与红线交织在一起——一个可见,一个不可见。 它们共同构建起一种延续的象征结构, 连接起身体与声音、物件与记忆、个人与群体。 因此,这个摇篮不仅是一个家庭物件, 它成为了一个代际共鸣的象征空间, 在其中,情感、血脉与文化的纽带彼此交织。

通过《摇篮》,王雨思考了母系关系中那种脆弱却持久的连接。

她用物质与声音的交织,展现出身份与记忆并非固定不变, 而是不断被时间、情感与文化重新编织的过程。

In this installation, Yu Wang combines a traditional Mongolian cradle with red thread and a recording of her grandmother singing Mongolian folk songs.

In Mongolian culture, the cradle symbolizes motherhood and protection – it is where life begins, the space where a child first feels the rhythm of home. Yet in Yu’s work, the cradle is tightly bound by red thread – a chord that both protects and restrains, hinting at the complex emotional tensions spanning generations of women.

The grandmother’s voice in the recording lends the piece an intensely, intimate warmth. Yu shared that in Mongolian tradition, a lullaby is not merely a song, but the very sound of memory. It carries the continuity of language, emotion, and culture. When she embeds her grandmother’s voice into the installation, sound becomes an invisible thread, intertwining with the red thread – one visible, one invisible. Together, they construct a symbolic structure of continuity: connecting body and voice; object and memory; individual and collective.

Thus, the cradle transcends from being a mere household object, but rather transforms into a symbolic and embodied space of intergenerational transmission – where bonds of emotion, bloodline, and culture intertwine.

Through ‘Cradle’, Yu contemplates the fragile yet enduring connections within matrilineal relationships. By weaving together materiality and sound, she reveals that identity and memory are not fixed identities, but rather multi-sensory processes continually re-woven by time, emotion, and culture.

In her work, thread serves both as a symbol of connection and a vessel for memory, and reveals that the ‘thread’ in this exhibition transcends mere visual symbolism, embodying an emotional and cultural bond — a metaphor that tightly weaves together private experience and collective history, the female body and cultural identity.

“本作品延续了我对文化身份断裂与“失落”的探索。在此创作中,我将传统的蒙古摇篮与电子显示屏结合,用红线将其捆绑成象征性的“结”。这种捆绑不仅是物理上的束缚,更是家庭关系中情感张力的深刻隐喻。缚结使摇篮与屏幕形成不可分割的联结,而屏幕上两人玩绳游戏的动态影像,则象征着人际关系的复杂性与冲突性。

“This work continues my exploration of the rupture and ‘loss’ of cultural identity. In this piece, I combine the traditional Mongolian cradle with an electronic display screen, binding them together with red yarn to create a symbolic ‘knot’. This binding is not only a physical restraint but also a profound metaphor for the emotional tension within familial relationships. The binding creates an inseparable connection between the cradle and the screen, while the image on the screen, showing the motion of two people playing string games, symbolises the complexity and conflict in human relationships.

当两人动作从有序渐趋混乱,画面传递的情感波动亦从亲密转向纠缠,从秩序走向失序,映射出家庭或亲密关系中潜藏的张力与不稳定性”

As the actions of the two individuals shift from order to chaos, the image conveys emotional fluctuations from intimacy to entanglement, from order to disorder, reflecting the underlying tension and instability within family or intimate relationships.”

七宗罪

the seven deadly sins

虞添锦tianjin yu

添锦成长在一个典型的中国式家庭,父亲在外工作,母亲承担了几乎所有的家庭事务。后来母亲重返职场,却依然要同时兼顾家庭与事业。添锦从母亲身上看到了女性的坚韧与包容,也意识到社会对女性角色的隐形期待。这些经历深深影响了她的创作视角,使她的作品始终带有鲜明的女性意识。

Yu grew up in a traditional Chinese family where her father worked outside and her mother took care of almost everything at home. Later, when her mother returned to work, she still had to carry the double burden of both career and family. Through observing her mother’s resilience, Yu developed a strong awareness of women’s strength and the invisible social expectations placed on them. This female perspective has deeply influenced her artistic practice:

镜子 油画

Mirror, oil painting

2m x0.8m, 1.65m x 0.6m, 0.8m x 1m, 0.8m x 1m, 0.6m x 0.8m, 0.5m x 0.7m, 0.5m x 0.5m

我的家庭是比较传统的中式家庭,一直延续着“男主外、女主内”的模式。以前,妈妈主要负责家里的大小事务和我跟弟弟的教育,爸爸则一心在外工作。

后来妈妈重返职场,但家里的分工并没有随之改变。我爸爸是比较典型的传统中国男性,带点大男子主义,几乎从不过问家务事。所以妈妈那段时间特别辛苦,既要全身心投入自己的工作,又要包揽家里所有琐碎的事——每天做饭、打理家务,还要盯着我和弟弟的学习,里里外外都是她一个人在扛。

(其实我家的这种情况,在当下中国挺普遍的。现在时代确实不一样了,男女都有自己的工作,很多女性也在职场上发光发热,但“家务事默认属于女性”的观念,好像还是一种隐形的约定俗成。) 最让我佩服的是,我妈妈明明要在工作和家庭之间连轴转,内外都操持,却依然特别理解我爸爸。她经常跟我说,爸爸在外工作也很辛苦,从不会抱怨这种分工的不公。 在我眼里,她真的是个内核特别强大的女人。不是说她从不疲惫,而是即便承担着双倍的压力,她依然能以包容的心态去体谅家人,用自己的力量把家里的一切都打理得很好

从小到大,家里一直是妈妈主要负责照顾我,我们相处的时间也最多,所以在我的创作里, 我特别习惯从女性视⻆出发去思考和表达。 比如我之前做的探讨少女情绪的作品,就是完全以女性视⻆切入的。我想通过这个作品,去 挖掘当下时代里,社会对女性的那些隐形规训——比如对少女外貌、行为、情绪的各种“应 该”和“不应该”,而这些思考,其实都源于我从小在妈妈身上、在自己成⻓过程中感受到的 女性处境。

I come from a fairly traditional Chinese family that has always followed the pattern of ‘men work outside, women take care of the home’. My mother was mainly responsible for all the household matters and for raising my brother and me, while my father focused entirely on his career.

Later, my mother returned to work, but the division of roles at home didn’t change. My father is a typical traditional Chinese man with a touch of male dominance—he almost never gets involved in housework. During that time, my mother was under a lot of pressure. She had to devote herself fully to her job while still taking care of everything at home: cooking, cleaning, and helping my brother and me with our studies. She carried it all on her own shoulders.

Actually, this kind of situation is still quite common in China today. Even though times have changed and both men and women have their own careers—many women even shine in their professional fields—the idea that ‘housework naturally belongs to women’ still seems to be an unspoken rule.

What I admire most about my mother is her strength. Even when she was constantly switching between her job and home responsibilities, she always understood my father. She would often tell me, “your dad works very hard too”. She never complained about the unfairness of it all.

To me, she is a woman with incredible inner strength. It’s not that she never feels tired, but even under double pressure, she stays patient and caring, holding our family together with her quiet power.

Since my childhood, my mother has always been the one taking care of me, so we spent the most time together. Because of that, I naturally tend to think and express from a female perspective in my art.

For example, in my previous work about the emotions of young girls, I approached it entirely from a woman’s point of view. Through this piece, I wanted to explore the hidden social expectations placed on women today — those silent “shoulds” and “should-nots” about how girls should look, behave, or feel. All of these ideas come from what I ’ ve observed in my mother and experienced myself growing up as a girl.

我这个探讨少女情绪的作品,表现形式是这样的:我先把 7 种不同的少女情绪,一一绘制在镜子上,接着将这些镜子打碎,最后再把破碎的镜片一片片贴回到少女的身体上。

对我来说,镜子本身就像少女审视自我的窗口,而打碎的镜片,既象征着外界规训下被割裂 的情绪,也暗喻着少女在各种期待中破碎又试图拼凑的自我。当破碎的“情绪镜子”与身体重 合,其实是想呈现女性在成⻓中,那些被忽略的情绪如何烙印在身上,又如何在困境中寻找 自我完整的过程。我本科的专业是油画,当时我的老师经常跟我说,不要把创作局限在传统的画布上。他总鼓励我,试着把身边的任何东⻄都当成“画布”,因为对承载作品的“画布”的 选择,本身就可以带有象征性的意义。

正是老师的这番话,让我在创作时不再被单一的媒介束缚。就像我这次用镜子做载体,其实 也是受了他的启发——镜子不再是简单的“画布”,它本身的“反射”“易碎”属性,正好能呼应我想表达的少女自我审视与情绪破碎的主题,比在普通画布上创作更有张力。

我把绘制好情绪的镜子打碎,这个灵感其实来源于一句话:“比蒙娜丽莎更美的是燃烧中的蒙 娜丽莎”。

众所周知,蒙娜丽莎是经典的、静态的,她的微笑带着一种永恒的美,但燃烧时的艺术品, 带着破碎与消逝的张力,反而更有直击人心的力量。这和我想表达的少女情绪很像——完整 的镜子就像被规训后“完美”的状态,而打碎的瞬间,那些被压抑的、割裂的情绪才真正显现出来,这种破碎的美感,比完整时更能传递我想探讨的女性成⻓中的挣扎与真实。

“In this artwork exploring the emotions of young girls, I used the following process: I painted seven different emotions onto mirrors, then shattered the mirrors, and finally attached the broken mirror pieces back onto the body of a girl.

To me, the mirror represents a window through which girls examine themselves. The shattered pieces symbolise emotions fragmented by social expectations — the feeling of being broken and yet trying to piece oneself back together. When the fragments of ‘emotional mirrors’ are placed on the girl’s body, it reflects how those ignored emotions become imprinted on her, and how she seeks wholeness in the process of growing up.

My background is in oil painting, and my professor often told me not to limit my creativity to a traditional canvas. He encouraged me to treat anything around me as a potential ‘canvas’, because the choice of medium itself can hold symbolic meaning.

His words freed me from the constraints of a single medium. Using mirrors as my material was inspired by that idea — the mirror’s reflective and fragile nature perfectly echoes the themes of self-reflection and emotional fragmentation I wanted to express. It gives the work much more power and tension than a flat canvas ever could.”

永恒的针脚

Timeless stitches

王 雨 Yu wang

这个项目既是与祖母的对话,也是一种意识的传承。祖母多年的教养已融入我的血液。知识的匮乏并未影响她的态度与信念。这次,我教她认自己的名字,并请她教我如何绣出她的名字。这种简单的对话方式打破了传统的展览模式,将我带回了童年生活的场所。

“This project is a conversation with my grandma, and it is also a kind of inheritance of consciousness. Grandma's years of upbringing have penetrated my blood. The lack of knowledge has not affected her attitude and beliefs. This time, I taught her, her name. And I taught her how to embroider her name. The simple dialogue method breaks away from the traditional exhibition mode and returns to the place where I lived when I was a child."

刺绣与表演

Embroidery and Performance

可变尺寸

Variable size

这件作品是《永恒的针脚》, 是一件基于影像的装置作品,记录了王雨与她外祖母共同完成刺绣的过程。 她告诉我,从小她就穿外祖母亲手绣的鞋垫。 在这件作品中,她们用两根针、一根红线,同时绣出两只鞋垫—— 外祖母在一边绣传统的蒙古图案,而王雨在另一边绣外祖母的名字。 这根红线从一只鞋垫穿过另一只鞋垫,物理上将她们的动作连结在一起。

红线在这里既是工具,也是一种象征。 它传递着语言、手艺与血脉的交融。 她说,这些线并不是整齐的,而是缠绕、拉扯、甚至有些混乱的—— 就像真实的亲缘关系一样: 在婴儿时期,母系之间的线紧密相连; 随着成长,线被慢慢拉长; 而在青春期或成年的阶段,这根线的张力会加剧, 既有想要靠近的温情,也有渴望独立的冲突。

即使身处远方、求学海外,这根线依然存在。

它也许变成了电话的电线,也许化为记忆的回声, 但始终没有断开。

通过这件作品,王雨把刺绣这种日常的、女性的劳动行为转化为代际情感与记忆传递的隐喻。

红线成为情感的语言——一种凝固的时间、一种流动的记忆。

这件作品揭示了母系关系如何在手工劳动与生活经验中被持续地编织与传承。

In Yu Wang’s work, the thread is not merely a material, but a metaphor and structure of emotion and memory – symbolising the bonds, inheritance, and continuity between mother, daughter, and grandmother.

With the embodied practice shared between Yu and her grandmother, the thread becomes a living entity – connecting the shared memories and care of generations of women.

This video-based installation documents Yu and her grandmother embroidering together.

Yu Wang shared that she wore her grandmother’s hand-embroidered insoles from childhood. In this piece, they used two needles and one thread to embroider two insoles simultaneously – her grandmother embroidering traditional Mongolian patterns on one side, while Yu stitched her grandmother’s name on the other. The red thread passes through both insoles, physically linking their movements.

Here, the red thread serves as both tool and symbol. It conveys the intertwining of language, craftsmanship, and bloodline. She explains that these threads are not neat, but tangled, pulled, even chaotic — much like real kinship: in infancy, the maternal bond is tightly woven; as children grow, the thread gradually stretches; and during adolescence or adulthood, its tension intensifies—a tug between the warmth of closeness and the pull toward independence.

Even when far away, studying abroad, this thread persists. It may become a telephone cord, or an echo of memory, yet it never breaks.

Through this piece, Yu transforms the everyday, feminine labour of embroidery into a metaphor for intergenerational emotion and memory transmission. The red thread becomes the language of feeling — frozen time, flowing memory. Revealing how matrilineal bonds are continuously woven and passed down through manual labour and lived experience.

消失的女性

disappeared women

冯颖茹 YINGRU FENG

在颖茹的家乡——陕西北部的农村,土葬仍是最普遍的丧葬形式。

墓碑上所镌刻的,只有逝者本人、其子及孙辈的名字——女性的名字往往从这片土地的实物记载中被抹去。

尽管女性的遗体与记忆已融入这片土地,但由于她们的名字从墓碑这一实物记载中消失,后代对她们的纪念也变得困难重重。

颖茹看到后辈们渴望纪念女性祖先,却因无法找到她们身份与生平的文字记载,只能雕刻一些图案,这些图案让人想起通过口述历史流传下来的母系祖先的名字。

在作品《消失的女人》中,颖茹对这片承载仪式感的土地进行了一次短暂的干预:她竖立起冰制墓碑,观察它们逐渐融化,以此纪念那些被时光遗忘的女性,并凸显她们从历史记载中消失的现状。

In Yingru’s hometown in the countryside of northern Shaanxi, earth burial remains the most popular form of burial.

Memorialised through tombstones, it is only the names of the deceased, his son, and grandson that are recorded – with the names of women often being erased from the physical record in the landscape.

Whilst the bodies and memories of women are embedded in the landscape, commemoration of them by their descendants has been challenged by their disappearance from the physical record, documented via tombstones.

Observing desires to commemorate female ancestors, Yingru witnessed descendants carving motifs reminiscent of their matrilineal ancestors’ names passed through oral histories – unable to discover written documentation of their identities and lives.

In ‘Disappeared Women’, Yingru momentarily intervenes with the ceremonial landscape, erecting tombstones of ice and observing their melting - commemorating the women lost in time, and recording their erasure from the physical record.

视频、冰雕

Video, ice sculpture

可变尺寸

Variable size

对我来说,我妈妈和祖母都是一个旧世界的坚决的卫道者,就像我做创作,非常诱发我触发我做创作的其中一个事件,是在我们每年的各种盛会清明节以及各种的祭祀当中,我奶奶都会说你去代表我们家人去给神灵上一个布施,然后到时候你给完钱了以后,你就写你爷爷的名字,或者说你写爸爸或者伯伯的名字,我说为什么?他们就会说因为他们是一家之主,这是应该做的,他们会代表我们一家人。我觉得他们是在无意识地巩固一个以男性长辈,不能说是霸权,但是是以男性长辈为中心的一个家族集体。

在我成长当中,我一直认为这是一件非常天然的或者正确的事情,直到我开始认识我家族之外的各种的长辈以及各种不同职业的女性,她们带给我一些新的启发,就我才能够认识到女性是可以以其他的形式,以其他的一个状态存在的,而不是以一个附庸者。所以他们对我作品的影响让我认识到他们其实是我所作品当中消失的一环,他们的无意识的行为或者是说他们认为对的事情是在加剧他们这个消失的过程,或者是说让消失这件事情得以传递下去,是这样的。

“To me, both my mother and grandmother were staunch defenders of the old world. One pivotal moment that inspired my creative work occurred during our annual Qingming Festival celebrations and ancestral worship rituals. My grandmother would always say, “Go represent our family and make offerings to the deities. After you’ve paid the money, write your grandfather’s name, or perhaps your father’s or uncle’s.” When I asked why, she would explain that as the family head, it was their duty to represent the entire clan. I believe this practice unconsciously reinforced a patriarchal family structure—though not through dominance, it centred around male elders as the family’s guiding force.

Throughout my upbringing, I had always believed this to be a natural or correct notion. It wasn’t until I began meeting elders from outside my family and women in various professions that I gained new perspectives. These encounters revealed to me that women can exist in different forms and states, rather than being mere appendages. The influence of these women on my work essentially made me realise they were actually missing links in my creative process. Their unconscious actions or what they perceived as right actually accelerated this disappearance, perpetuating the cycle of vanishing.”

蝴蝶效应

the butterfly effect

冯颖茹 YINGRU FENG

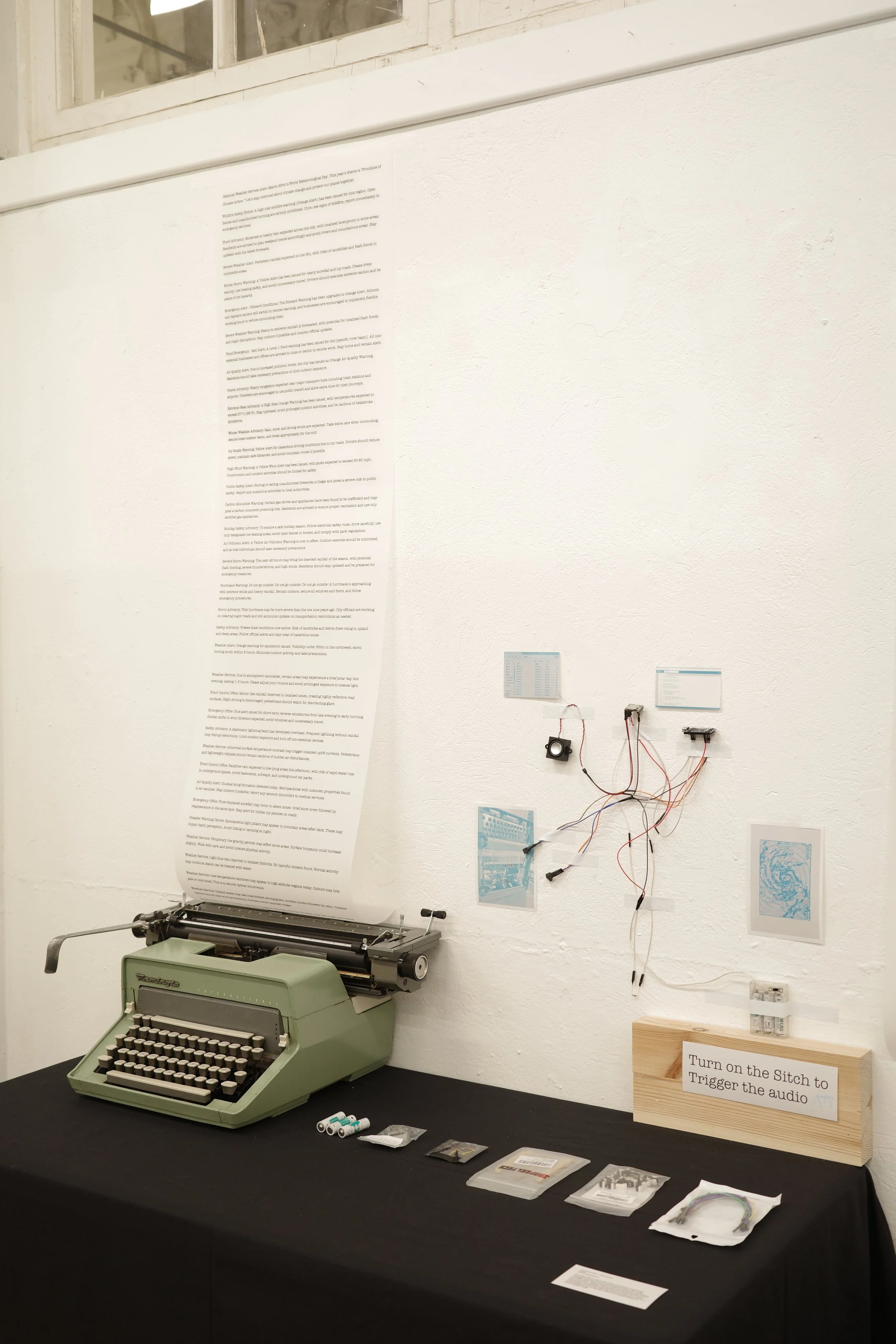

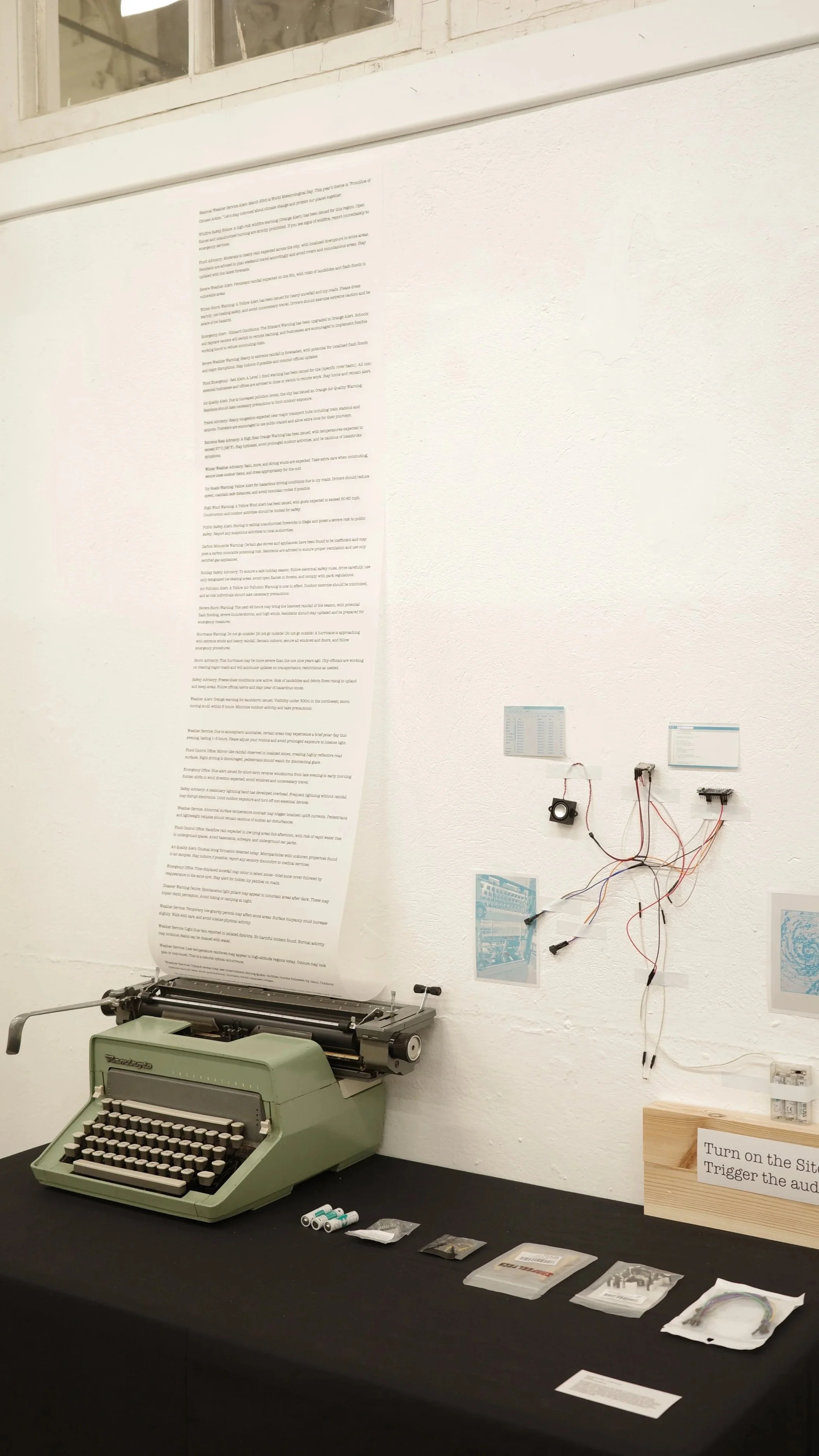

这件作品,是选用传统打字机结合声音装置而组成的装置艺术。每摁下一个字母,就会传来来自艺术家颖茹家乡的天气预报。

这是一件关于记忆与乡愁的艺术作品。在颖茹的记忆中,她的家乡——陕西,每天都会为当地的人们发送天气预报和短信,有时极端天气会变成电话通知。“但我感触最深的是,不管我在哪里,就算现在我在英国,我的手机里依然能收到来自家乡的天气预报,好像我在这里重新活了一遍一样,家乡从来没有忘记我。这种小小的短信就像蝴蝶振翅一样微弱,但对于异乡的游子却能激起强大的波澜,所以我给它取名《蝴蝶效应》。”

观众摁下的每一个字母都代表着不同的天气情况,传过来的播报声不仅仅有中国普通话,还有陕西当地方言,似乎都在暗示着陕西人民,你们的背后还有一座陕西。打字机也不仅仅是交流的工具,而是重塑称为家乡的羁绊,牢牢捆绑住游子的心。

A work about memory and homesickness, ‘The Butterfly Effect’ combines a traditional typewriter with a sound device. Each time a letter is pressed, a weather forecast from Yingru’s hometown fills the air.

The installation mirrors Yingru’s daily reality of her hometown administration in Shaanxi sending daily weather forecasts, and extreme weather warnings to its citizens - even when they’re living overseas. When speaking about this work, Yingru said “what touches me most is that no matter where I am, even now in the UK, I still receive weather updates from my hometown on my phone.

It feels like I’m living a part of my life here all over again, as if my hometown has never forgotten me. These tiny text messages are as faint as a butterfly’s wingbeat, yet they stir up huge waves in the heart of a wanderer—that’s why I named this work The Butterfly Effect."

Each letter pressed by the audience corresponds to a different weather condition. The broadcast sounds that follow are in both Mandarin Chinese and Shaanxi dialect, as if whispering to the people of Shaanxi: ‘you always have Shaanxi standing behind you’. The typewriter is more than just a communication tool; it is a reborn bond to hometown, tightly tying the hearts of overseas travellers to their roots.

This work speaks to aspects of the curatorial rationale behind 'Xian - A Thread. All artists and curators share the experience of being international students, who are continuing to build embodied archives through matrilineal relationships via digital means - continuing familial proximity and creation, despite geographical distance.

With all artists and curators sharing the experiences of being international students, the format of the digital platform was chosen to reflect that we are all continuing to build an embodied archive through our matrilineal relationships via digital means, continuing familial proximity despite geographical distance, and continuing the body as site of creation and storage.